Dear The Futurological Congress,

Have you ever met someone who made you laugh so hard while you were with them, but then when you went home they had you pondering the meaning of life, and whether or not society is barreling toward its own destruction? That’s what it was like getting to know you. On the surface—hilarity. Underneath—did you actually just articulate what is wrong with everything?

Let’s start with the jokes.

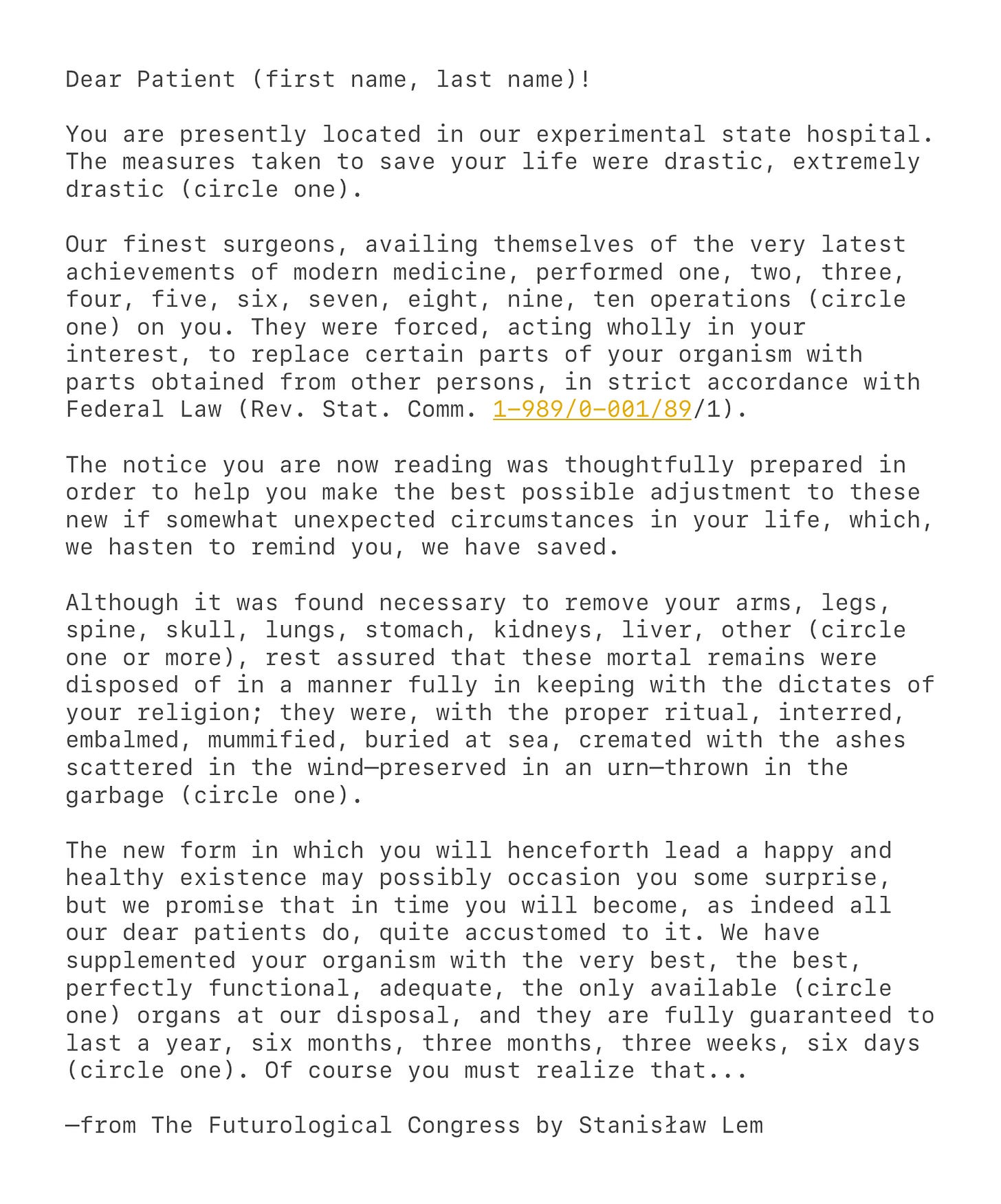

To set the scene, we must be aware that we’re living in a society so technologically advanced that the normal rules of mortality no longer apply (this may be why it’s so over-populated). In this world, you might get abducted by political revolutionaries and, thinking you’re hallucinating, you might act braver than you should and get yourself nearly killed. Then your friends might attempt to save you via helicopter, and the helicopter might blow up with you inside it. After that, instead of immediate death, you might experience this:

“I came to and found myself in a jam. Cranberry jam, awfully sour. I was lying on my stomach, with something large and fairly soft crushing me. A mattress. I kicked it off. Pieces of brick were digging into my knees and palms. I propped myself up, spitting out cranberry pits and sand. The room looked as though a bomb had hit it. The window frames jutted out, jagged slivers of glass protruding from their edges, pointing to the floor. The overturned hospital bed was charred. Near me lay a large printed card, smeared with jam. I picked it up and read:

In such a world, not only can we live longer, we can also experience whatever emotional state we wish, on-demand:

“An enjoyable evening, but someone played an idiotic trick on me. One of the guests—I wish I knew who!—slipped a little gospel-credendium into my tea and I was immediately seized with such devotion to my napkin, that I delivered a sermon on the spot, proclaiming a new theology in its praise. A few grains of this accursed chemical, and you start worshipping whatever happens to be at hand—a spoon, a lamp, a table leg. My mystical experiences grew so intense that I fell upon my knees and rendered homage to the teacup.”

In addition to being able to feel ecstatic spiritual bliss any time we want (or any other mood), we’re no longer limited to fragile, human bodies—we can now purchase absolute aesthetic perfection.

“‘If prostheticism is voted in, I assure you, in a couple of years everyone will consider the possession of a soft, hairy, sweating body to be shameful and indecent. A body needs washing, deodorizing, caring for, and even then it breaks down, while in a prostheticized society you can snap on the loveliest creations of modern engineering. What woman doesn’t want to have silver iodide instead of eyes, telescopic breasts, angel’s wings, iridescent legs, and feet that sing with every step?’”

Of course, it’s not all a party. In such a society, you end up having problems with your too-intelligent computers:

“Spent the whole afternoon ingesting a most remarkable work, The History of Intellectronics. Who’d ever have guessed, in my day, that digital machines, reaching a certain level of intelligence, would become unreliable, deceitful, that with wisdom they would also acquire cunning? The textbook of course puts it in more scholarly terms, speaking of Chapulier’s Rule (the law of least resistance). If the machine is not too bright and incapable of reflection, it does whatever you tell it to do. But a smart machine will first consider which is more worth its while: to perform the given task or, instead, to figure some way out of it. Whichever is easier. And why indeed should it behave otherwise, being truly intelligent? For true intelligence demands choice, internal freedom.”

Isn’t it nice to think that maybe the worst thing that happens with AI is that robots start trying to weasel their way out of doing the tasks we give them? And maybe crime becomes less gory when you can simply trick people into living a complete illusion, getting rid of them forever.

“Mindjacking is usually difficult to detect. The victim, given the appropriate drug, is led into a fictional world without the least suspicion that he has lost contact with reality. A certain Mrs. Bonnicker, desiring to dispose of her husband, a man inordinately fond of safaris, presented him on his birthday with a ticket to the Congo and a big-game hunting permit. Mr. Bonnicker spent the next several months having the most incredible jungle adventures, unaware that the whole time he was lying in a chicken coop up in the attic.”

Even though you had me laughing, it all hits a little close to home. You may have written these words in 1971, but they feel oddly prescient.

Still, as the lawyer in your narrative asserts, evolution is its own corrective.

“‘A dream will always triumph over reality, once it is given the chance. These, sir, are the casualties of a psychemized society. Each of us knows that temptation. Suppose I find myself defending an absolutely hopeless case—how easy it would be to win it before an imaginary court!’

Savoring the fresh, tart taste of the Chianti, I was suddenly seized with a chilling thought: if one could write imaginary poetry and build imaginary homes, then why not eat and drink mirages? The lawyer laughed at my fears.

‘Objection overruled, Mr. Tichy! No, we are in no danger of that. The figment of success may satisfy the mind, but the figment of a cutlet will never fill the stomach. He who would live thus must quickly starve to death!’”

Somehow, this isn’t exactly a comfort.

I really did enjoy our time together, even if it includes an underlying concern— where is the great slingshot of time and technology hurtling us? Don’t get me wrong; the social progress is real, and I’m grateful for the ways my children get to live in a world that doesn’t wholly despise them for being themselves. Or at least, I hope that’s the trajectory; every day there’s a new sadness for all the ways it’s still not true. In any case, I would never go back to 1971, or any other time.

Still, it haunts me that given the choice between the advertised dream and reality, we somehow choose the dream every time. In the dream, we get to be comfortable in our chairs, we get to curate how others perceive us, we get to interact in the ways we choose, with little risk or apparent consequence. And for now, that dream isn’t even that compelling. It’s a social feed or an expensive avatar or a VR headset or a not-too-smart AI companion.

But what about when the dream gets better? People say that’s a good thing, “just you wait!” But I don’t know. Because when it gets better, what will happen to our ability to choose what’s real over the dream being pitched to us? Or will mindjacking not even be a potential crime, because we’ve already chosen to mindjack ourselves?

Anyway…heh…back to the jokes!

“Progress is a wonderful thing of course, and I can appreciate the lactiferins that are sprinkled on the pasture to turn the grass to cheese. And yet this lack of cows, however rational it may be, gives one the feeling that the fields and meadows, deprived of their phlegmatic, bemusedly ruminating presence, are pitifully empty.”

Nothing like a good cow and cheese joke to get things back on an even keel. You’ll come back soon?

Yours,

Sarah Avenir

P.S. If you’ve not yet read The Futurological Congress by Stanisław Lem, I strongly recommend you do so, post-haste! Especially if you enjoy laughing, or pontificating on the ramifications of technology on our future selves.

P.P.S. In the spirit of POSSE, this was also published on Mastodon, Twitter, and Instagram.